|

Glossary recently met with San Francisco based artist Erik Parra at his Minnesota Street Project (MSP) studio. Parra is one of four artists recently awarded a residency at MSP, sponsored by Liquitex, as part of their Research Residency Program. The program coincides with the July 2017 release of their Cadmium-free heavy body paints. The award included a studio space for three months and hundreds of dollars’ worth of Liquitex product for the artists to use. We approached this Review as Dialogue as a studio visit, and got a sneak peek at the work in progress for his upcoming solo exhibition at Eleanor Harwood Gallery, March 3rd. We talked about emotional resonance, paintings within paintings and politics of subject-matter. Enjoy! Glossary – We are recording; it’s on! Erik Parra – Me, me, me, me, me . . . Can you hear me? G – The first thing I notice in looking around the space is all of the blue tape, which is particularly interesting because it looks like you are using the tape not only to mask off areas, but as a palette too. EP – I realized that when I am trying to glaze an area, the tape is getting in my way, I started using it as a palette and dabbing on it. Especially when I “Virgo-out” and get really into a small area. It’s really humid with the recent rains, and it takes forever for the paint to dry . . . G – When did your residency start? EP – I got the keys on December 5th, but I couldn’t start right away because I got pneumonia! But I got a lot of rest, and listened to my mom and didn’t go in the studio right away because I really wanted to get well and maximize my time once I got here. It drove me crazy because I don’t like sitting still—if I can’t work I am in torture! Unless of course I am watching a riveting film . . . G – Like film-noir? EP – Oh yeah, I am a huge film noir fan. G – Visually, you are really capturing the film-noir atmosphere in your work; we’ve talked about that before. Did I notice on your Instagram that this is the biggest painting you have worked on in a while? [points at large canvas] (pictured above) EP – This is the largest painting I have done since grad school in 2004. Ryan Mc Junkin made the stretchers for me. G – But what about your installations that you have done; haven’t you done bigger things? EP – Well, this is the largest stand-alone two-dimensional painting . . . Yeah, in Reno I did a 9 foot tall painting on Tyvek that wrapped around the whole space. It was called This: A Contemporary Situation, and was installed at the University of Nevada Reno. I had to paint it 12 feet at a time, and roll it up and paint the next 12 feet. I used a traditional straight-up scale drawing to do it. When I got in the space I touched it up. Inside I built a stadium that you could enter out of shipping pallets, it was 11 feet; that was the largest installation I have made. G – But when it comes to paintings, you’re used to working in a more intimate size. EP – The challenge is to make the idea translate no matter what size. The primary viewer is going to see this online, in a jpg, so I want the shapes and scale to translate. The other challenge is working in acrylic, the paint dries fast, so covering large areas is a different practical experience than covering small areas. You don’t think about it until you start working on it, and then you realize, “Wait a minute—the paint isn’t acting like it usually does.” I have been doing a lot of work with spray, too. And in my other studio I am used to spraying, but here we have to take the work outside to spray. G – Is everything I am looking at finished? EP – There is a lot of work in progress here, although some of the smaller works are finished. Function Follows Form #1, and Function Follows Form #2, for example. Most of them are pretty close. G – I noticed there are a lot of mirrored compositions—is that new for you? EP – No, I’ve been working on that for a while. The "filmic" inspiration with these is the twins from The Shining. You have two things that are similar but different, that are creepy and disconcerting. I am pushing that idea a little further, and there are literal mirrors in some of the paintings. [the paintings do not include actual mirrors, but images of mirrors that have been painted into the composition, with objects “reflected” across the rooms onto the painted mirrors.] G – There is also repeated subject-matter, such as these two plants, one for each canvas. EP – Yeah, I had this thought the other day that this is the first time . . . so, before this I have been working on interiors, and the idea came to me the other day that all of these images are from one “house” or place. It’s less about mapping out all the rooms of the house, or even a dream house [but about these singular rooms]. G – It’s an imaginary place, though. When you are in that space mentally, when you are working in this place, are you imagining people, and stories of their lives? I don’t think I have ever seen people in your work. So for example, this painting of a bedroom with the ruffled sheet is very different than the moody and stoic rooms I have seen your past work. EP – Yeah, so I have been thinking about the notion that there might be a narrative without dictating the narrative. I was thinking about on one end of the spectrum I could for example have this room with blood splattered on the floor and that would be a very specific narrative, but I don’t want to prescribe the narrative. So much of the work is completed after the work is viewed and discussed [by others]. I don’t want to tell you what the narrative is, but I want to put things in there that you, the viewer, can find or imagine for yourself. In some of the work, there is also a filmic device of zooming in—we are getting a close look at one detail of a room. G – So are there any imaginary characters that are playing out roles when you work? EP – Sometimes, yes. For example, recently at City College [where Parra teaches] we received a bunch of materials from a woman whose husband had passed away—he was an architect. So, I don’t normally have a story that I check in on, but I was thinking about these works around the idea of making this dead architect a fictional hero; but it’s not that specific. I even made an effort to not research architects who may have passed away in San Francisco because I wanted to maintain that sense of ambiguity. For example, the furnishings in my work reference specific designers or an era, but I change it slightly so that it removes the ego of the designer so that it is just another "modern chair". Some aspects of this work is about the shift from modern to contemporary, which was a very controlled intellectual movement based on controlled obsolescence, based on patterns of consumption. Because if you have something that is always contemporary, then as a consumer you always have design options to outfit your house. There are always new things to buy. That’s more of the story that I think about when I am painting—that a bunch of guys sat around, ‘How can we make more money? Well, we can make furniture cheaper'. G – 'And we can make new ones every year!' EP – 'And we can build it so it's disposable too—that it’s not worth moving and you have to buy new things when you move!' I am definitely interested in the failed utopia of modernism, but I’ve been ditching talking about that with the work because I am more interested in the cultural nostalgia that surrounds the idea of these people sitting around and deciding our lives. And more importantly, [this cheapness and disposable-ness] was so detrimental to artisans and craftspeople. I have had people read my artist statement and ask me, “How am I supposed to think about 1960s radical politics when I look at this work?” Well, it’s not meant to be a specific story from that time, about a particular person—they aren’t illustrative—they aren’t illustrating. I’ve been thinking about history painting; history painting tends to be allegorical, where you have these characters that arranged like in a play—that are fixed. In those cases, the painter becomes this kind of director that has fabricated this aspect of the history allegory. But I’m just selecting—I am picking and choosing things that don’t have a fixed allegorical position. So, going back to this bedroom, the decision to make the sheets ruffled, and to set the lighting at a certain time of day is getting close to a what seems like a particular narrative, but I don’t want to get too specific, like gives clues to a scene—like the clock set a 6:45 am or anything like that. G – Yes, these aren’t a specific moment in time; they are an era, an ethos. EP – Right. G – Because there are no people, the viewer is forced to recall history in a broader sense: What was happening during mid-century modernism, during the early part of the Cold War; what has happened after the Cold War ended—with consumerism, with capitalism, and domestic issues. Speaking of which, I never see kitchens in your work. EP – I focus on a lot of “leisure” spaces. I feel that the minute I include a kitchen in the work I am going to risk getting into gender politics. Part of the reason that I don’t use the figure was because in the past I used the figure in my painting, and the minute I would have someone in my studio they would want to talk about racial politics. If they had any stake in the game or any soap box to get on my paintings became an entryway for them to talk about their own issues. G – A typical grad school experience . . . EP – Yeah, it would be comments like: “You’re Mexican, why can’t I tell you are Mexican by looking at your paintings?” So, removing the figure was a conscience effort. Now, if I put in figures the paintings might be less “creepy” [moody], but I feel that the way they are now has more emotional resonance without people. G – There is something there now so that the viewer can enter the painting . . . [pointing to unfinished area] There is so much happening right here. EP – That’s the painting within the painting. It’s moments that I leave in there, when you get to see all the way through to the underpainting. It’s a composition within a composition. I like to leave a trail of breadcrumbs all they back to the beginning. In other works I have another smaller painting on the wall of a room for example, and it’s its own painting within the painting. G – So, what do you think of the colors and the new paints that you got from your Liquitex prize? Some artists are very driven by their materials, such as using only discarded house paint, or only a particular brand for its texture and colors. EP – I really think they have it all covered . . . I can’t tell the difference between the new cadmium-free colors and the originals. I don’t have brand loyalty to paint, but I do like some of the new things I was able to try and will continue to use them. What I do is a fair amount of research on the pigments, and used a lot of Golden before this—their heavy body paints. But with Liquitex my favorite things I have been able to try are the paint markers, the fluid paints, and the ink. They also released a line of “muted” colors which I will definitely be adding to my palette—I love these off-colors—they’re just really great colors right out of the tube. G – You have a show coming up; what has it been like in the studio these days, and trying these new things? EP – I have been cranking in the studio full time for a while because I was off from teaching for the holiday break. The only way I could have done the show with Eleanor [Harwood] so soon is because acrylic dries so fast. G – I notice that there are a lot of cut-outs as well. Are you hand cutting the shapes that you use? EP – I use a variety of hand-cut stencils. It’s a riff on the traditional approach to creating illusionistic space on the canvas. Controlling edges that are next to each other, making close edges crisp and far away edges softer . . . but I am using those techniques much looser, in a more contemporary way. Some new things I have been doing are incorporating new rooms, such as the bedroom . . . and I have been compressing and removing perspective and messing with the architecture so you can’t tell where the walls end or begin. G – That gives an unsettling strangeness to the spaces. EP – Yeah, they are technically spaces that could never exist. And like my other shows, I might be incorporating some elements that come from the paintings into the space. It’s not a one-to-one object, like my show at state or Sam Freeman in late 2016. G – When you create sculpture, you are pulling the narrative off the canvas, you’ve made a three-dimensional space for people to inhabit. You have a room, and the paintings are part of that fabricated scene, which also have their smaller included elemental paintings. So how do we explain that—is it the 4th wall, like in a movie? Would you be perhaps exploring film as the next phase of the installation? EP – I am not exploring film or photography with this work. Many times the shows are set up so that when you entered the room you were entering a painting; there was the installation, the paintings on the wall and the paintings within those . . . logically it can’t go anywhere else, this is where I am at right now. More information:

Erik Parra, History by Choice March 3 - April 14, 2018 Eleanor Harwood Gallery 1275 Minnesota Street, Suite 206 San Francisco, CA 94107 Tuesday 1-5:00pm Wednesday – Saturday 11am-5:00pm & by appointment *First Saturday of every month, open until 8pm More information on the: Liquitex Research Residency Program.

0 Comments

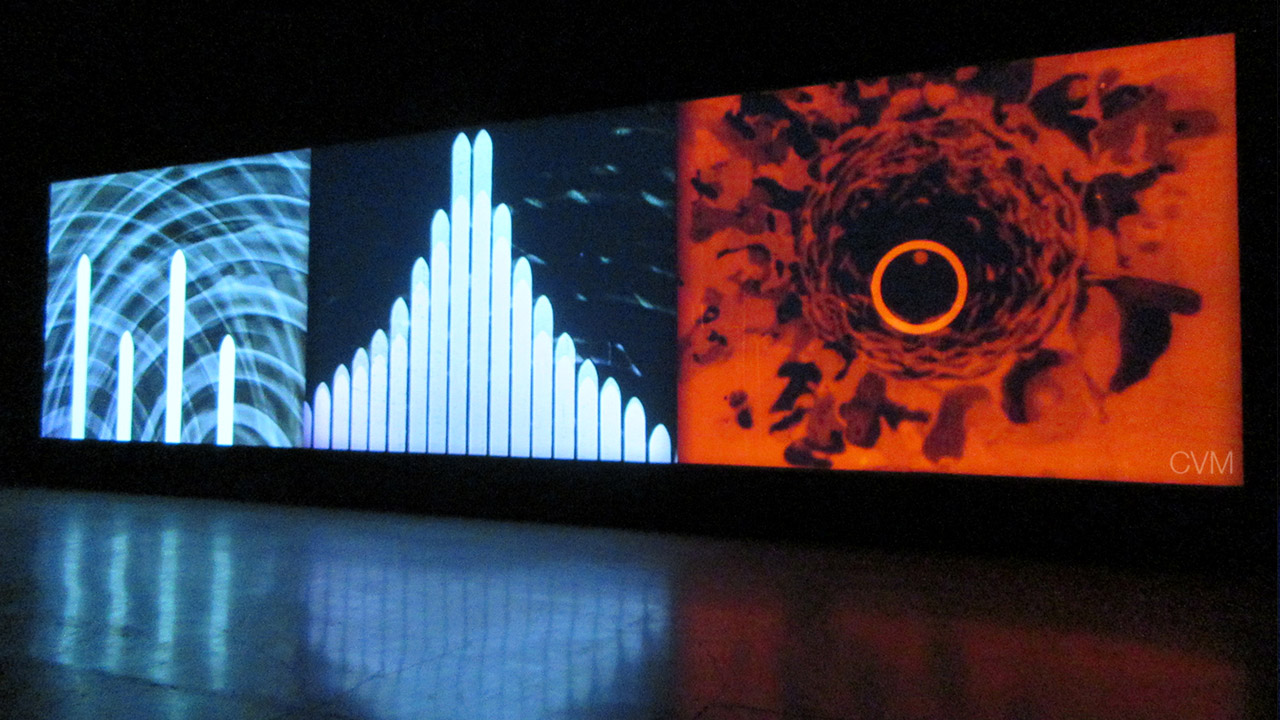

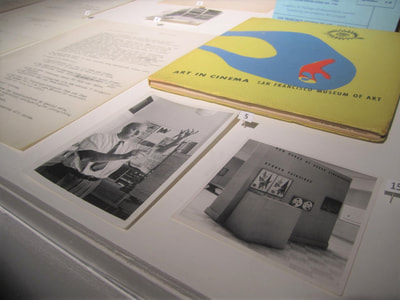

Review as Dialogue: Cindy Keefer of Center for Visual Music on Oskar Fischinger @ Weinstein Gallery2/6/2018 Oskar Fischinger Raumlichtkunst, (c. 1926/2012) [SPACE LIGHT ART] Three projector HD reconstruction by Center for Visual Music. Open until February 10, 2018. Weinstein Gallery SoMa 444 Clementina Street San Francisco, CA Gallery hours: Tuesday–Saturday: 10 am–5 pm Sunday & Monday: By Appointment (415) 362-8151 On January 31, Glossary attended a talk at Weinstein Gallery on the work of avant-garde filmmaker Oskar Fischinger, presented by Cindy Keefer, Director of Center for Visual Music (CVM). The talk coincides with an exhibition featuring a 3 projector HD reconstruction of Fischinger’s Raumlichtkunst, (c. 1926/2012) created by CVM. This highly recommended exhibition introduces one of the most influential film-makers of the avant-garde, whose work is a precursor to animation, music videos and advertising graphics. As per the exhibition catalog, “Fischinger is recognized as the father of Visual Music, the grandfather of music videos, and the great-grandfather of motion graphics.” Over fifty films and 800 paintings comprise his production legacy, much of which is archived and curated by CVM, as well as held in several collections around the world. For this Review as Dialogue, we took a slightly different approach than in previous versions: it’s a paraphrased excerpt of the talk peppered with quotes from Keefer. Enjoy: Weinstein Gallery is the first west coast gallery to exhibit Raumlichtkunst, (c. 1926/2012). “It is Roland Weinstein’s dream to open this second space in SoMa and to present work like this to the public—free—because we believe that art should be for everyone,” says Managing Director and Curator, Kendy Genovese. Previously Raumlichtkunst traveled to Len Lye Centre/Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand, the Whitney Museum of Modern Art, New York, Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, Australia, Palais de Tokyo, Paris and the Tate Modern. Many other works by Fischinger have been presented worldwide; to learn more about this and other projects by CVM, a comprehensive list can be browsed on the events page of their website. Center for Visual Music (CVM) is a non-profit archive dedicated to visual music, experimental animation and abstract cinema. They are based in the Los Angeles area, and are in the process of relocating to Northern California this year. “We preserve, curate … we are dedicated to education, scholarship, new research and distribution of the film, performances, media, and research in this tradition, as well as and related documentation and artwork,” states CVM Director Cindy Keefer. "We have the world's largest collection of Visual Music resources," says Keefer. They manage the films of Oskar Fischinger, Jordan Belson, Mary Ellen Bute and others. In addition they also have significant collections in the genre of visual music such as the original research of Dr. William Moritz, works by Richard Bailey and Jules Engel and photography by Hy Hirsh. They have curated exhibitions worldwide that feature objects and film from their collection. Part of their mission is to restore films, funded by some government grants, occasional museum funding and private donations. “Basically we are always fundraising because we always have films to restore! We always have old volatile [film] nitrate, we always have old decaying films that are fading,” quips Keefer. The audience chuckles, as those who are all too familiar with non-profit institutions and art restoration can attest: the work just keeps coming, and the need to ask for funding is a constant. What is Visual Music? “Our definitions are rather historical," says Keefer. There are many definitions of visual music that Keefer shared with the audience, including a brief history and a few examples excerpted here. "For nine decades visual music was a term to refer to films that had a very strong interrelationship between the visuals and the music. This term was also used by art critic Roger Fry, around 1912 to refer to a painting [1], but as far as film, no one used the term until the 1930s to refer to visual music.” Visual Music has a long and ancient history that dates back as far as Aristotle and Pythagoras’ “Music of the Spheres.” The history of visual music performances began in the 1730s with Color Organs, machines and harpsichords that were modified so that one could assign a note to a particular color. The earliest visual music film is dated approximately 1912 in Italy. Visual music film that we are familiar with today including contemporary music videos, advertising and even early Hollywood animations—stems from the Absolute Film Movement which began in Germany in the 1920s—which Fischinger was a part of.  Raumlichtkunst (c.1926/2012) installation view, Weinstein Gallery, 2018, image Glossary Magazine. Raumlichtkunst (c.1926/2012) installation view, Weinstein Gallery, 2018, image Glossary Magazine. Film historian William Moritz, who is Fischinger’s biographer, defines visual music as: “a music for the eye comparable to the effects of sound for the ear.” “He (Moritz) asks us to contemplate,” says Keefer, “what are the visual equivalents of melody, harmony, rhythm and counterpoint.” “Visual music is a time-based structure similar to the kind or style of music,” says Keefer. “A new composition created visually, but as if it were an audio piece—it can have sound or exist silently.” Fischinger’s Ornament Sound drawings fall into the category that describes visual music as, “direct translation of images to sound.” True visual music creates a relationship between the visuals and their meaning and interpretation as carriers of sound—directly opposite from music videos, which apply visuals to already existing audio. Fischinger’s Visual Music Oskar Fischinger is German American artist, born in 1900 (Germany) and died in 1967 (Hollywood). His first love was music—he studied violin. While many painters were turning to film as a way to activate their paintings, Fischinger was creating film by activating music; he made many films, some silent and others accompanied by live organists. Fischinger believed, that from Raumlichtkunst, all arts would merge from this new art: “Plastic, dance, painting, music become one,” he wrote. Comprised of hundreds of successive drawings or animation created by arranging objects, Fischinger’s process is testimony to the rigor and dedication of fully actualizing purely analog, abstract film—making it the epitome of time-based media. Before Raumlichtkunst was created in Munich, 1926-1927, composer Alexander László was touring a series of performances titled Farblichmusik (Color Light Music) using projected images with his color organ piano, the “Farblichklavier” (spectrum-piano). He invited Fischinger to show his abstract animations at his concerts to give the performance more dynamism and a modern flavor. The critics loved the films, but panned the music! Needless to say, their working relationship came to an abrupt halt after the disparate ravings. Fischinger went on to create his own performances, sometimes using up to five simultaneous projectors and 3 screens, accompanied by live percussionists. Early iterations were called “Raumlichtmusik” (Space Light Music), but critics encouraged him to change it to “Raumlichtkunst” (Space Light Art). Now, audiences can see a completely digitally restored/reconstructed version of Raumlichtkunst. The visual restoration is based upon the history of tinted film available in Munich during the 1920s, and research on Fischinger’s use of color in his other work. As previously mentioned, the originals included live percussion music accompaniment—but no recordings of these exist, nor complete listings of the performers who may have been present, and there is no written documentation of the music. The CVM appointed music historians to research hypothetical music choices for that time—who would Fischinger have heard, or been exposed to in Munich in 1926? Research did not glean any definitive results because in general, avant-garde music was not being recorded. Through the historian’s recommendations the CVM reconstruction of Raumlichkunst includes the first known percussion recording of that era, Ionisation by Edgar Varèse (1929) and two versions of Double Music by John Cage and Lou Harrison (1941), a nod to Fischinger’s negotiations with Cage to produce a soundtrack for a different project encouraged in the 1940s by Hilla Rebay of the Guggenheim Foundation that ultimately was never realized. Below is an example of Double Music. (note: audible music starts at 00:18) Amadinda Percussion Group, J. CAGE-LOU HARRISON: DOUBLE MUSIC (San Francisco, April 1941) · Zoltán Kocsis · John Cage · Amadinda Percussion Group, Legacies 2: Works for Percussion Vol.1 ℗ 1999 HUNGAROTON RECORDS LTD. In the spirit of how Raumlichtkunst would have been performed live or toured in the late 1920s, the CVM version changes constantly. Using three different film loops that are off-set and each running at different times, the combinations of images that the viewer sees will never repeat. The music is not live, it is also designed to weave in and out of visual changes. Though the film is the feature of the exhibition, also on view are works on paper that comprise other films, in addition to examples of this Ornament Sound drawings, ephemera and photographs. On view until February 10. Notes:

[1] The work of Wassily Kandinsky, in this instance a reference to “color music.” “The improvisations become more definite, more logical and more closely knit in structure, more surprisingly beautiful in their colour oppositions, more exact in their equilibrium … They are pure visual music; but I cannot any longer doubt the possibility of emotional expression by such abstract visual signs.” Spalding, Francis. Roger Fry, Art and Life, (Berkeley: University of California Press), 1980, 168. This year CVM has released a new DVD of Fischinger's work, which is available for purchase! Dedication: When Glossary visited Raumlichtkunst earlier this month, we chatted with Genovese about some of the exciting film and sound artists that are working in the Bay Area today, including Paul Clipson, Joshua Churchill, John Davis, Chris Duncan and others. This weekend, as we were developing content for this article we learned that Paul Clipson tragically and unexpectedly passed away on Saturday, February 3. This article is dedicated to him. |

Reviews

All

shop

Eco-mindful journals by Glossary Syndicate

glossary's FOUNDER & author

thank you for visiting

Consider making a donation to support operating costs, research & writing time. Any amount helps!

reviews

All

other sf art publications

SFAQ

Art Practical Articiple SF Art Enthusiast SF Weekly SF Gate/Chronicle SF/Arts (Monthly) Stretcher Sartle global sf coverage

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed